My Story

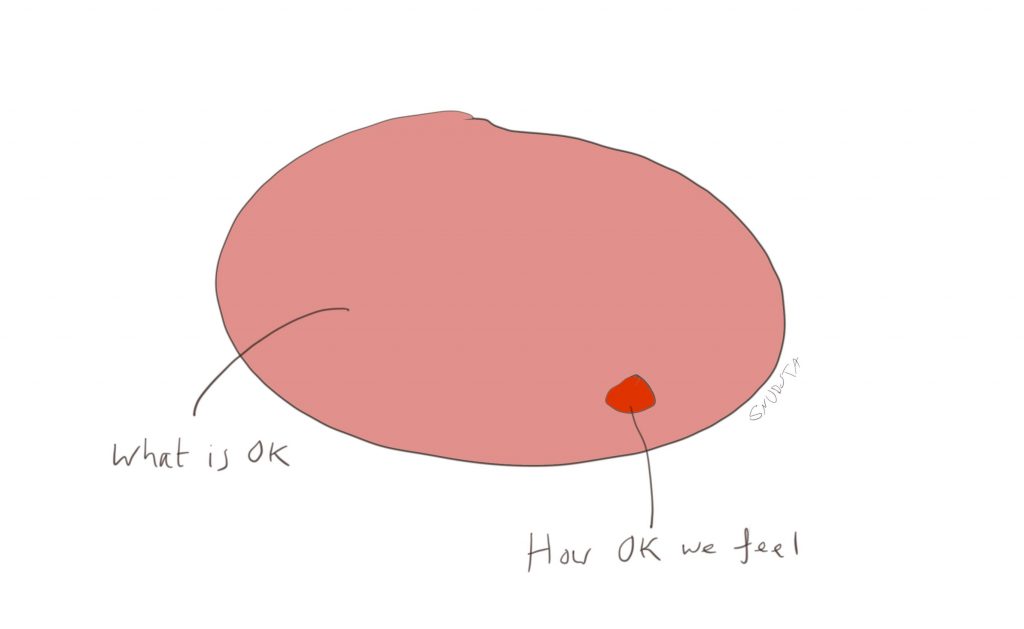

Everyone wants to feel OK. We want to be happy.

So we do everything we can to feel better – to be OK. That’s why we buy things, or drink wine, or build businesses. It’s why we notice the good stuff and want more of it, and we notice the bad stuff and want it to go away.

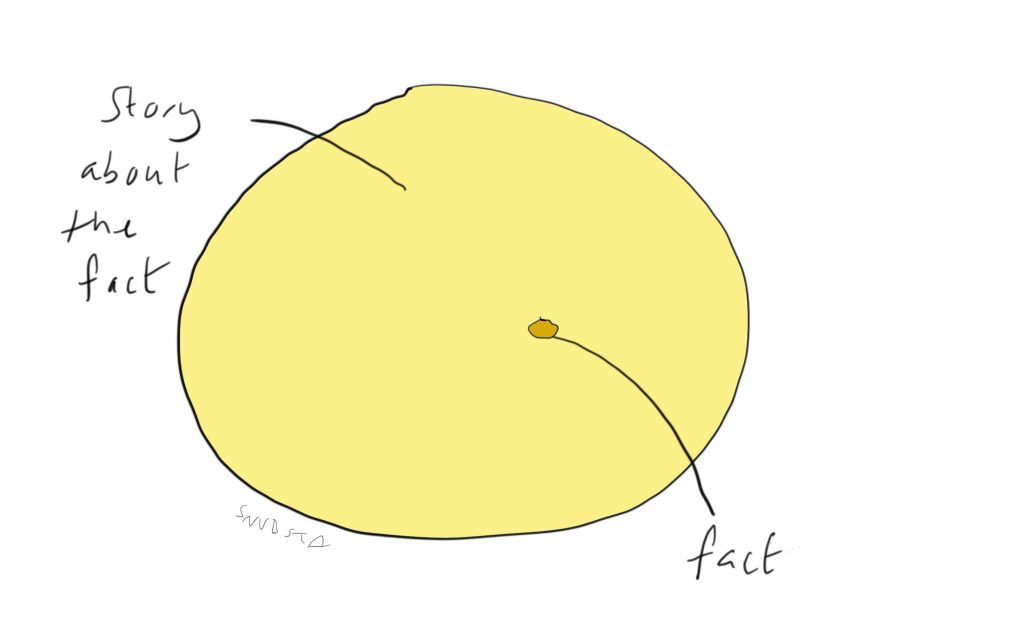

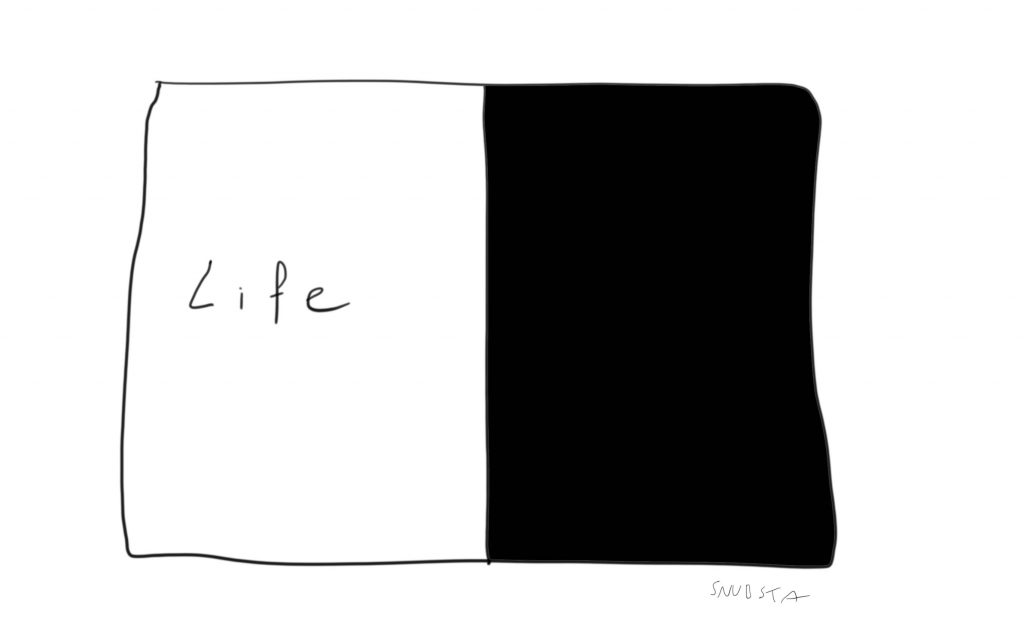

The thing is, all this activity drowns out a simple fact: Everything is OK as it is. We just have to stop and notice it.

And when we do “unlearn” all the stuff society teaches us about what’s good and what’s bad, what’s OK and what’s not, we see that this real OKness goes deeper than anything we’ve seen before. It feels like this deep, unshakable, unquestioning love.

I grew up in a family that was all about ballet. My brother wanted to be a dancer – and for him it was all-consuming. Me? I was on the sidelines figuring out things for myself.

I remember going to cub scout camp – and hating it. The tent full of loud kids, the toilets dug into the ground. The loneliness of a crowd far from home.

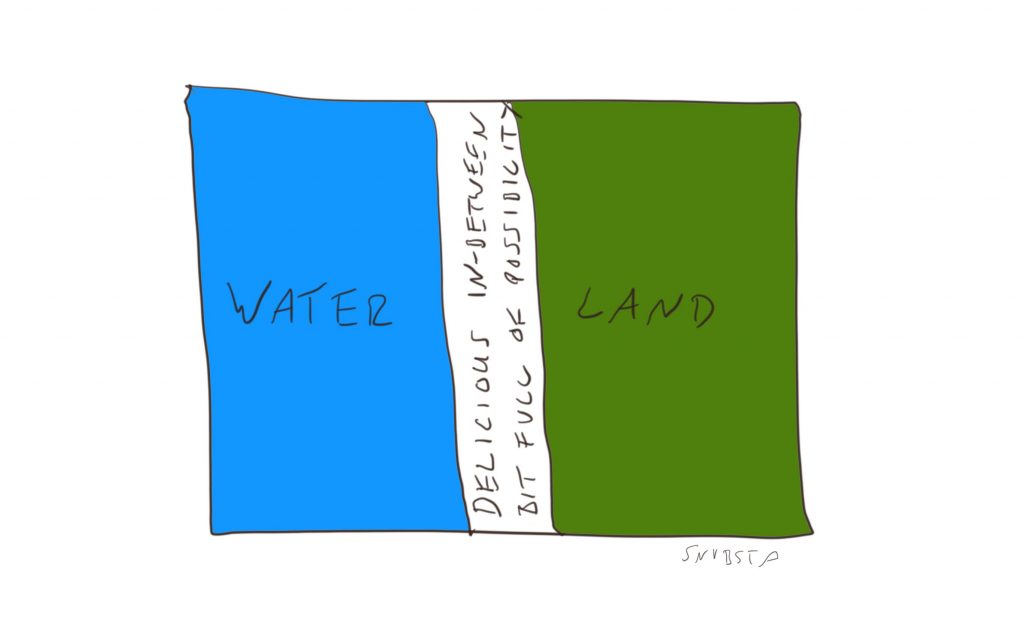

I was happiest on long walks with my family through the marshy lands of eastern England. I loved the quietness, where I could think my dreams. There was something magic about this place where the land met the sea – the birds seeking worms in the oozing mud. Sometimes land, sometimes sea – really neither. Here I was relaxed and full of ideas.

I made my own museum from things I’d found on these walks: rocks, tree bark, crab shells. My prized exhibit was a bony vertebrae. I loved its four pointy corners and its airy honeycomb.

I remember the first time I realized I would die one day. It felt like a rush of coldness that started in my belly and swamped my arms and legs. I remember wanting that feeling to go away and so I tamped it down so I would never have to feel like that again.

These big questions kept bubbling up though. I recall talking with my dad about what came before the Big Bang – was it nothingness or was it God? It was a big question and he had no answer. Neither did I, and the huge, vastness of the question made me feel strange when I contemplated it.

But I was also a child of the eighties, when our culture was all about making money to buy that faster car and bigger house. The trains from Ipswich ran into Liverpool Street, right in the middle of London’s financial district. My mum thought it would be a good idea for me to get a job as a financial trader and work in one of the glittering towers.

Instead I got into journalism at university. I liked the idea of thousands of students seeing my name above an article. We’d work all night putting the paper together, then we would help deliver it around the campus. I felt a little famous – like I was doing something important… something with status.

I had a few jobs in journalism. One was for a daily morning paper in Birmingham – but I hated crushing my social life to meet the 11pm press deadline. I had to get away.

This job in Amsterdam came up. It was the year 2000 and the dot-com boom was on. It was an adventure and I thought I could get rich. As a student, I had lived the best year of my life in Spain – maybe this would be the same.

And so I found myself, at the age of 29, on the management team of an internet start-up, responsible for 13 editors and reporters, including former national newspaper and TV journalists from the UK, the US and Australia.

It all looked good, but it was a time of inner turmoil. The thing is, I’d been avoiding addressing my sexuality for years. Not just avoiding it, I’d buried it deep somewhere inside, hidden from sight by a hard shield of denial.

But in the Netherlands, I was working with other gay people and saw that it was OK to be me.

And so I had the chance to see myself… for the first time.

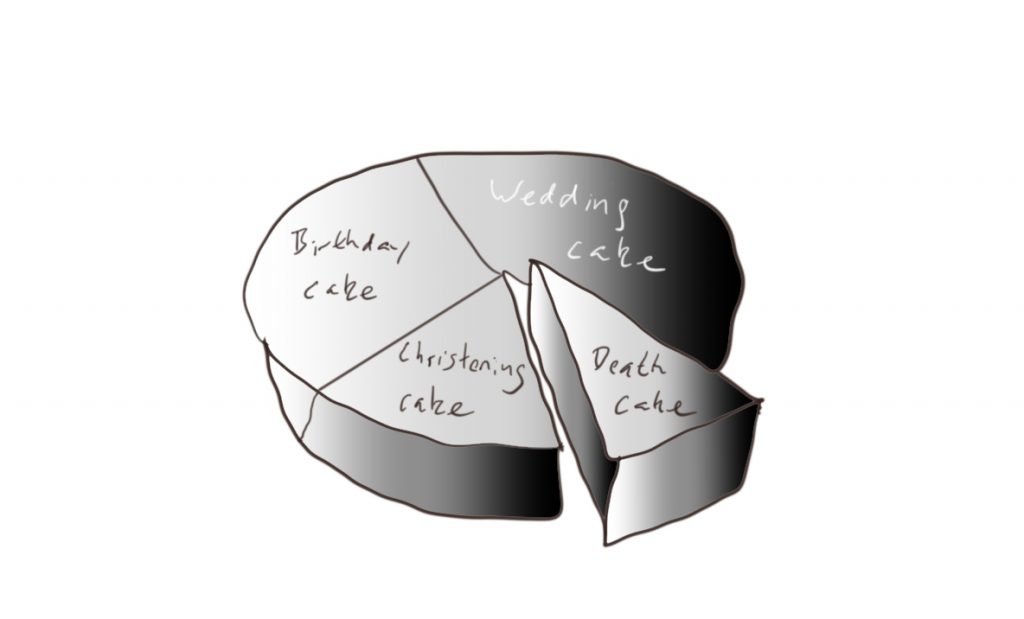

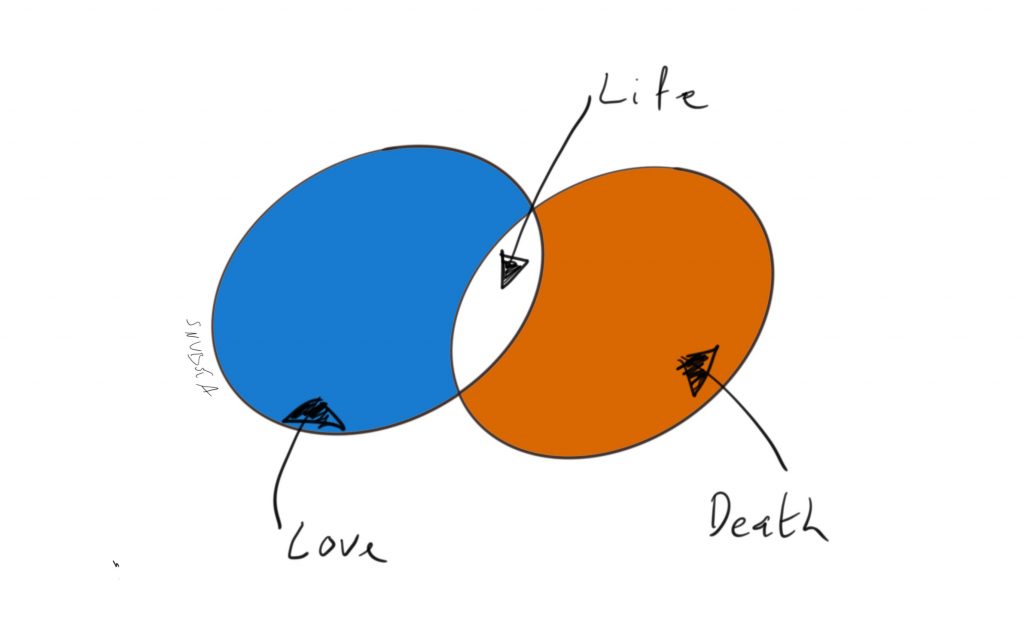

Fast forward a few years, I met a wonderful Canadian man called Bram and moved to Ontario. We planned to get married in July 2005, but shifted the date forward a month because Bram’s father was in palliative care – his cancer was beyond cure. My parents rushed across the Atlantic and my brother listened in by phone from England as Bram and I wed in the roof garden of Toronto’s Princess Margaret Hospital. There was cake and the nurses had some. Bram’s father died two days later.

I took a job at the Toronto Star – a dream gig for anyone in journalism. But it didn’t work for me. I left after six months because I couldn’t stick the lack of freedom at this big newspaper.

So I started my own business. The internet was hot and I was seduced by the dream of “making money while sitting on the beach.” I liked the idea of this freedom and I was pretty sure I could build a solid business. And so I did. I had hundreds of customers and a team of 4.

Then in 2010, my website got hacked and my business got banned from Google – my flow of new customers immediately dried up. I got that sick feeling back – my chest and arms flooded with coldness. I was overwhelmed with fear, and I remember flinging my computer mouse in frustration, leaving a dent in the wall. Everything I’d worked for was about to collapse. Not only was it the end of my business… it felt like it was the end of me too. I felt I was going to die.

But it wasn’t and I didn’t. By 2015, the business was stable and profitable. I had that freedom – I could work when visiting Europe, or under the palm trees in Florida. This was the dream that the internet promised – my own business, under my own terms… wherever I wanted.

Something was still missing, however. I became obsessive about the company’s fortunes. I lived and died by daily sales – and one bad month would have me imagining I was on the way to ruin, soon to live by the road, penniless and friendless. That nagging anxiety took the shine off my days, damaged my relationship and left me wondering what was missing.

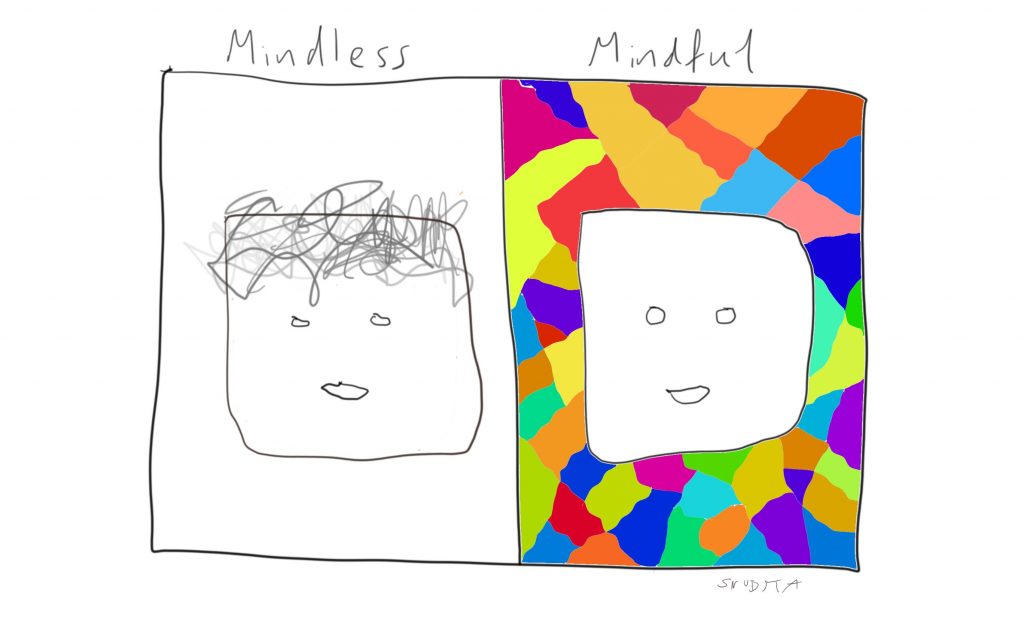

Then one day I discovered this woman called Julie on a webinar and joined her telephone training. I didn’t know what I was getting into, but the mind-training she provided made a difference. Little by little, my anxiety reduced – I stopped obsessing about the company’s results. I started to notice beauty in waving leaves and droplets on windows. I was a better listener, a better boss – a better husband.

When that summer a critical piece of software broke – software without which I could not deliver my product – I panicked. But then I noticed what I was doing and was able to stop and calm down. Eventually I gave myself the space to find a solution.

That October, I went on a retreat in California. Early one Sunday morning, I was out in the orchard, looking at one of the trees. It was crooked, stunted, almost leafless. And on its bark was lichen – that symbiosis of algae and fungus. Here was this half-dead tree supporting so much life – it was ugly yet important. I felt a flood of emotion from my chest at the beauty of it all – and I cried the rest of the day. When it was time to go home, I spent the six hour flight from San Francisco to Toronto looking out of the window and listening to Sarah McLachlan’s Ordinary Miracle on loop.

That Sunday, I came to realize how everything just works out OK. It all connects without me having to do anything. That OKness feels like love – a love so deep it overwhelms your body with well-being.

I realized that everything is OK just as it is, you just have to stop and notice it.

One night in July 2017 I was driving through the Ontario bush and four legs appeared in the car’s headlights. It was a moose. I stamped on the brakes but it was too late – the moose hit the car and richocheted off. I don’t remember this, but Bram told me I said: “I’m going to die, I’m going to die, I’m going to die” as we came to a halt.

After that incident everyone in my town said we were lucky to be alive. A driver had been killed in a moose collision on that same highway just a few months earlier.

I remember when I first met Bram, some 15 years earlier. It was probably my first experience of real love. I remember being next to him once and thinking: “I feel like I could die right now and everything would be OK.”

A few years later, when I was frantically building my business, my friend Chuck passed away of cancer. I don’t think I processed that death at the time. He was only 44 and I was too young to have friends who died.

Ever since my moment in the orchard, I’ve realized: death happens. We have to deal with it instead of denying it.

But what do we do with this knowledge? I obviously wasn’t OK with it when I hit the moose.

For me, part of the solution is seeing that truth without hiding it away under layers of denial. It’s about allowing it to be there, without wanting it to go away.

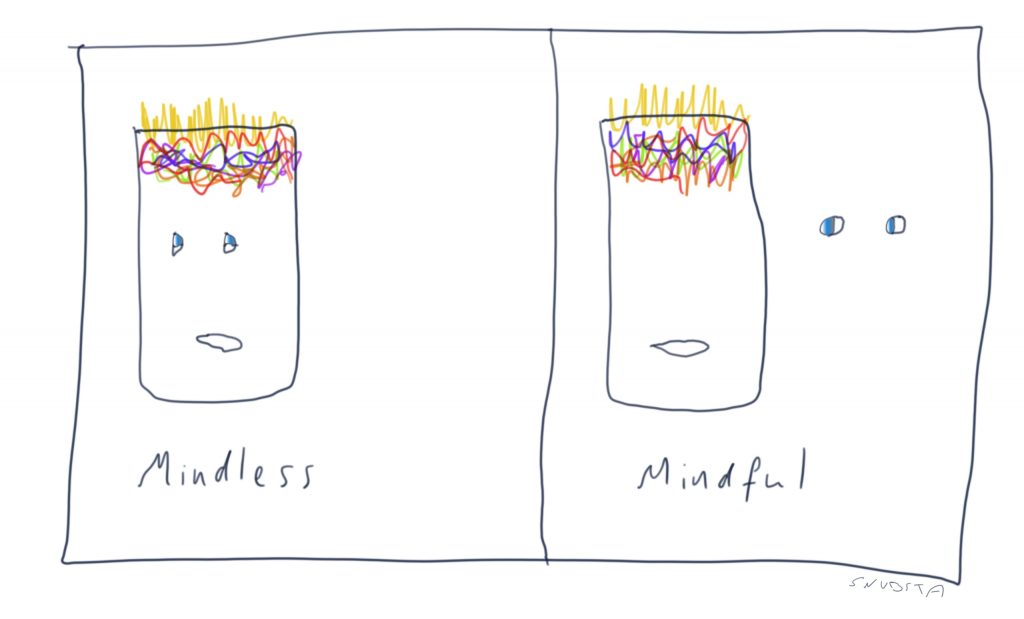

I discovered that once we notice our thoughts – our fears, our desires – we can sit with them. We can accept them. Only then can we notice the OKness that lies beneath our storytelling minds.

I don’t always get it right, but the training I went through made me less anxious because I was able to accept the good and the bad. And in doing so, I could feel the joy that’s present in everyday life when you’re OK with what is; OK with not being OK.

The police took nearly an hour to arrive after I hit the moose. While we were waiting, people living nearby came out of the woods with hunting knives and started to cut up the animal to fill their freezers. I guess it’s a practical way to deal with death. There’s an acceptance to it. People who live close up with nature understand that.

Children do too. They see and accept the reality of things without thoughts and stories getting in the way.

One winter morning in 2018, our boisterous nephew William was staying with us in Florida. As he stepped out of the front door, he was entranced by a flower. He just stared at it – still, silent.

After a while, someone said: “Do you know what that flower is called?” “It’s a hibiscus.”

And suddenly he snapped out of this noticing and was back in what we call real life, with its naming and its concepts and its thoughts.

But if you can learn how to stop – how to suspend judgement and narration for just a second – you notice that everything really is OK. The flower with its beauty that’s beyond a name. The tree that hosts life. The moose that provides food.

It’s all there and it all works. If we can find the space to notice.

The thing is, learning to notice takes time and practice. It requires the dedication to go to the gym and do the reps as we erase the old pathways of fear, grasping and denial that society treads into our minds.

This process of “uneducation” is sometimes painful – we see things that we have never seen before, and some of those things are difficult to look at.

But when we persevere, we start to really see…. and that’s when we notice the truth of OKness that underlies everything. The OKness that feels like the deepest love there could ever be.